An inside look at the location data industry and suggestions for reform

We'll take a look at the location data industry and explore solutions (both technological and regulatory) that address upstream and downstream problems.

In the US, there’s a collective learned helplessness when it comes to data privacy. We know it’s an issue, but privacy violations are so deeply entrenched into the way companies do business, that it feels incompatible to both participate in society (which requires using digital services) and protect your privacy.

The mobile location privacy problem has been festering in plain site for well over a decade, posing serious threats to peoples’ privacy and safety. This problem can be viewed as a subset of the broader issues of AI safety and fair use.

The problem spans how the data is sourced, sold, and used to make decisions.

Collection and sell-side: mobile location data is collected from individuals and sold to data buyers without meaningful consent or fair compensation to the individual. This shadowy supply chain disproportionately benefits the data brokers and buyers at the expense of the individual’s privacy and safety.

Sketchy use cases: data buyers (e.g. companies, state actors, criminal organizations, hackers) can weaponize the data against individuals (e.g. dragnet surveillance, bypassing warrants, consumer discrimination, identity theft and scams, stalking etc.).

Mobile location data has been on Congress’s radar since at least 2011. Senator Wyden’s website describes attempted regulation:

The bipartisan legislation [the 2011 Geolocation Privacy and Surveillance Act, GPS Act] creates a legal framework designed to give government agencies, commercial entities and private citizens clear guidelines for when and how geolocation information can be accessed and used.

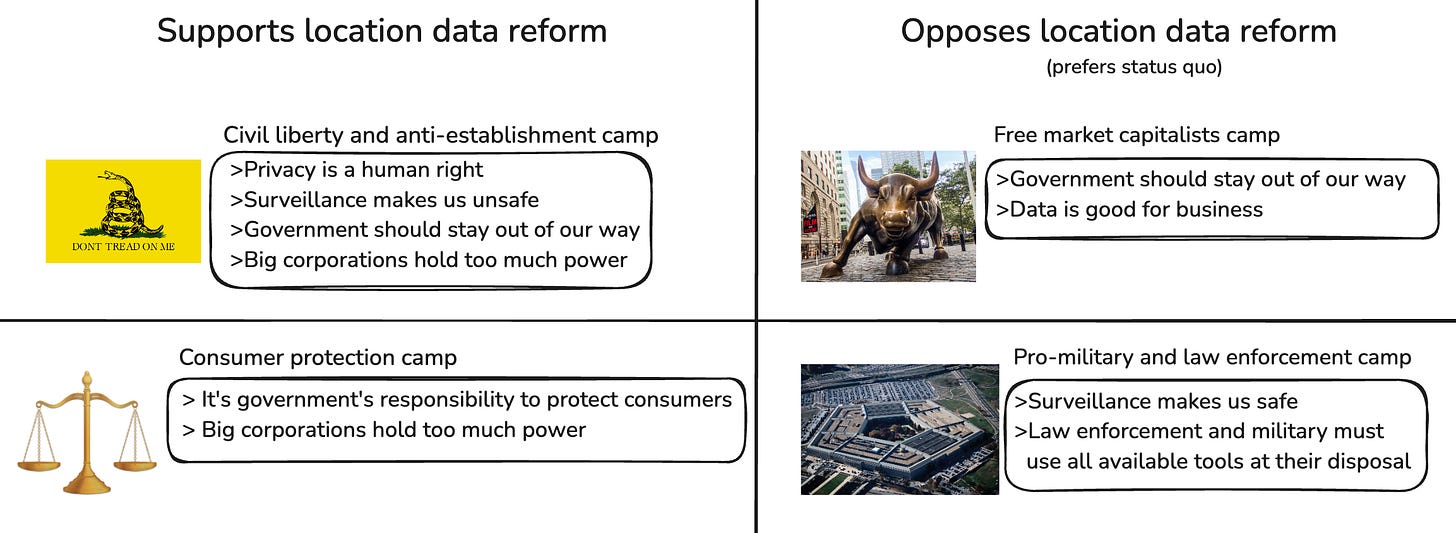

This issue is complex — both technically and ideologically.

The below diagram is reductive, but it is my attempt to group the different camps both for and against location data reform:

These different camps don’t fall strictly along Democrat and Republican party lines.

Opponents of reform have been winning for the past decade1.

In order to productively change something, it is helpful to understand how it works. In this post, I will try to demystify how the location data industry works. I will also share practical regulatory approaches that I believe can improve consumer safety and privacy. I’m not advocating for a ban of any kind — location data is a powerful tool that should be collected, sold, and used responsibly and transparently.

Here is a summary of the main points I will discuss:

Data brokers use a variety of methods to source peoples’ location data from their mobile phones with minimal transparency. Data sourcing is built on secrecy, not trust and transparency.

Regulatory action has failed to gain traction and has not been comprehensive.

I recommend mobile location data be regulated like healthcare data, which will increase user safety and deter excessive hoarding of sensitive data

SafeGraph

In this post, I am trying to shed some light on the opaque location data industry.

I worked for SafeGraph, a location data provider/broker, for ~8 months. My responsibility was working with technology companies, like Snowflake and AWS, to make SafeGraph’s data products easier for companies to evaluate and buy.

I was originally drawn to the company by some of the founder’s writing. From a 2016 SafeGraph blog post:

Google is one of the best AI and ML companies in the world. Why? Peter Norvig, Research Director at Google, famously stated that “We don’t have better algorithms. We just have more data.”

Michele Banko and Eric Brill at Microsoft Research wrote a now famous paper in support of this idea. They found that very large data sets can improve even the worst machine learning algorithms. The worst algorithm became the best algorithm once they increased the amount of data by multiple orders of magnitude.

Machine learning and artificial intelligence is fueled by data.

Good, high quality data serve as truth sets about the world from which our machines can learn. And most AI and ML is likely under performing because getting access to great truth sets is very hard.

And from a 2019 SafeGraph blog post:

[U]nless your company is Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Tencent, or 12 other companies … even analyzing all your data perfectly will only tell you about 0.01% of the world. If you want to see beyond your company’s pinhole, you will need external data.

As someone passionate about data analytics and software, these passages resonated with me.

Before joining, I researched the location data industry and became aware of its privacy problems. I discovered this article from The Outline that called out SafeGraph for violations of peoples’ privacy. The article references UCLA and Washington State University researchers using SafeGraph’s data to correlate peoples’ political affiliations with where they spent their Thanksgivings. This type of analysis uses device-level data, which is very private.

Before joining, I learned that SafeGraph no longer sells device-level data directly. Unfortunately, SafeGraph didn’t stop selling device-level data because of ethical concerns — instead it formed a new corporate entity called Veraset to do that.

From SafeGraph’s letter to a Congressional inquiry:

One of SafeGraph’s sources of data is its subsidiary, Veraset, LLC, of which SafeGraph is the majority owner. Veraset is a distinct legal entity, with independent contracting authority and a separate management team that controls its day-to-day operations

I liked that SafeGraph was no longer in the immediate business of selling device-level location data, but a corporate restructure doesn’t do anything to promote user privacy and safety.

A short time into my tenure, investigative journalist Joseph Cox dropped this scathing Vice article:

The Vice article definitely has some holes and appears to conflate device-level data with summarized foot traffic statistics. But overall, I believed the article raised many valid concerns.

SafeGraph did not issue a public response at the time.

By burying its head in the sand, I believe SafeGraph missed an opportunity to advocate for more transparency in the industry.

Nearly a year later, SafeGraph would rebut the Vice allegations in its response to a Congressional inquiry:

SafeGraph does not, and has never, used an SDK to collect information about mobile device users, location information or otherwise. This was true in June 2021, when the rumored ban was reportedly imposed.

Whether or not the location data was collected via SDK is more of a technicality and misses the point.

An archived Datarade announcement describes Veraset’s data sourcing:

Veraset is a foot traffic, mobility, and location data provider setting the standard for consumer privacy and regulatory compliance. The company sources its data directly from apps, SDKs, and aggregators across the globe. Before the data is packaged into data products, it undergoes significant cleansing, including deduplication, anomaly removal, and sensitive location filtering prior to delivery. In total, Veraset’s data offering spans 3 billion daily pings in the US, over 100 million DAU in the US, and 5 billion daily pings globally.

After I left the company, SafeGraph released a post titled It’s Our Moral Obligation to Make Data More Accessible:

We have a MORAL OBLIGATION to get this data into the hands of millions of innovators. Not doing so is a true failing of society. This data can save hundreds of millions of lives and help all of humanity … which means not using it hastens the death of hundreds of millions of people.

But there are hundreds of special interest groups fighting against it. They have good intentions. They know this data can make people’s lives better. But these special interest groups fight against making data more accessible to either enhance their profit, enhance their power, or just protect the status quo.

The post goes on to frame privacy as primarily an engineering challenge to be overcome with technology. There was no acknowledgement that it’s inherently impossible to create a “privacy-friendly” location data product without initial access to peoples’ private location data. When this information is routinely circulated, it increases the attack surface for hackers.

I’m all for advancements in privacy and security technology, but it must be paired with strict regulation to audit that the technology is being applied properly and the data is not getting into unauthorized hands. Even the best intentioned companies cannot be trusted to self-police.

The post goes on to promise a future of boundless innovation if only healthcare and financial data were also “democratized”:

What if we could combine pharmaceutical data with people’s physical records from their doctors, their hospital visits data, and the wellness data from their Apple watches? The leaps in pharmacology and physiology would be huge!

Imagine if we could combine anonymized IRS data and the Medicaid and Medicare data? By empirically tieing people’s financial wellbeing to their physical wellbeing, we could see all sorts of new programs. We could fund programs to direct public health initiatives right to the people who need it most.

Advancement in public health and policy alone would be mind boggling. There won’t be a question of how to best allocate resources. The data will all be there.

About a month passed after SafeGraph’s CEO published that manifesto before Joseph Cox dropped a second Vice article aimed at SafeGraph:

The online reaction was understandably strong, especially in light of the overturning of Roe vs Wade.

The article centered around hypothetical risks about selling data related to Planned Parenthood location, as opposed to a specific scenario where a known customer was purchasing this data for nefarious use. Nevertheless, this was an important risk to call out, and it prompted SafeGraph to remove these data points from its product.

SafeGraph addresses this article in the Congressional inquiry letter:

SafeGraph has removed all of the visit-related Patterns statistics aggregated to businesses categorized by the NAICS Code for family planning centers… Prior to removing the data, it posed no privacy threat to individuals because it only showed representative numbers of devices that visited a physical location within the NAICS Code. It did not show anything about any individual. It did not reveal anything about the services a user procured at such a facility, if they even entered it. Nor could it be used to infer any medical information about any individual. SafeGraph’s data could not be used to send targeted advertising because there was no device-level information associated with the data.

This episode reinforces how peoples’ location data needs to be treated and regulated the same way as healthcare data.

According to SafeGraph’s site, it appears they have replaced their location data with aggregated credit card spend data. Financial data has its own set of privacy concerns, but at least it’s way more controlled and protected than location data.

And according to the founder’s blog, it appears that Veraset was sold to an unnamed company.

With that background out of the way, let’s zoom out and discuss how the location data industry works.

Different names and levels of detail

Mobile location data brokers2 are companies that compile peoples’ mobile location data (i.e. GPS data from your smart phone) then sell access to this data to organizations, primarily businesses and governments.

Common names for how this data is marketed include:

mobility data

location data

GPS data (or GPS pings)

foot traffic data

footfall data

floating population data

The data is sold in one of the 2 formats:

device-level: this means 1 row of data represents a device’s location at a given point in time. This is very private, granular data.

place-level: data broker tallies up how many devices visit a certain point-of-interest or area-of-interest. This is less sensitive, but requires access to the sensitive data in order to build.

Follow the data (and the money)

Let’s breakdown how the location data industry works:

people use free mobile apps that require access to their location3

these app developers sell their users’ location data to location data brokers4

the brokers amass a large mosaic of user locations from many apps, forming a panel5

brokers may buy from other brokers to make their panel even fuller

access to the broker’s panel is sold to data buyers

Zooming in on the different ways the data moves from mobile apps to brokers

The are 3 main ways that peoples’ data gets sent to data brokers.

The specific apps being used to collect user’s location are often kept secret — both to the public and to the majority of employees at the data broker. If the name of the application were revealed, it would damage that app’s reputation. Users could also stop sharing their location with that app, and the data source would dry up for the broker.

Data sourcing method 1: Broker has their own app

Some data brokers run their own app in which they harvest and sell their users’ data. They typically then supplement this data by purchasing user data from other apps.

The company Foursquare is an example of a data broker that provides apps to end users, while also selling peoples’ location data to businesses.

Data sourcing method 2: Broker distributes SDK or API to mobile app developers

Data brokers can distribute SDK’s or API’s to mobile application developers to facilitate data collection. These SDK’s/API’s are essentially interfaces between a mobile app and a location data provider.

Apple’s App Store and Google’s Play Store can detect and flag the use of SDK’s they deem in violation of their privacy policies.

Privacy groups and the press have scrutinized this SDK-approach of data collection, As a result, it’s fallen out of favor. Unfortunately it’s been replaced with less traceable methods of data transmission.

Let’s explore a few controversial SDK’s of the past.

Pilgrim

Foursquare offered an SDK called Pilgrim — from their website it appears to be no longer active.

Exodus (a French pro-privacy organization) reports apps that have been tied to Pilgrim.

A class action lawsuit against Foursquare calls out the Pilgrim SDK.

OpenLocate

In a 2017 post, the Blackberry security blog made the following criticism about SafeGraph and OpenLocate:

In addition to “a device’s precise geographic location,” SafeGraph states they will also collect “other mobile identifiers such as Apple’s Identifier for Advertisers (IDFA), Google Android IDs, and other information about users and their devices,” according to their privacy policy.

With $16M in investment this year, it seems that SafeGraph is a force that will continue to thrive in an environment where users are being more open about sharing the data location in order to get location data, special features and unlockable items in apps.

Furthermore, the creepiness factor is cranked up to 11 by a recent blog post detailing their location collecting kit, OpenLocate. In this post, SafeGraph stated “OpenLocate is founded on the belief that developers should have complete control over how location data is collected on their users.”

The Yale Privacy Tracker describes OpenLocate:

The OpenLocate SDK will "collect location data (like GPS) from phones" SafeGraph, 04. This includes an Android and iOS SDK. The service is built to provide developers complete control over their location data. Developers can build location-enabled features into their apps and "maintain complete control over how end-user data is collected, where it is stored, and which APIs it will be sent to". This includes sending to storage services (like Amazon S3) or APIs (such as Google Places API or SafeGraph's Places API) SafeGraph, 05.

The archived OpenLocate Github page describes how mobile app developers can use the SDK to collect location data:

SafeGraph distanced itself from OpenLocate in a letter to Senator Warren, stating:

Shortly after the company’s founding and before its decision to focus its business on data about places, SafeGraph briefly explored the concept of an open source SDK called OpenLocate. The OpenLocate SDK was never functional. Independent contractors assisting in development of the beta-test OpenLocateSDK created a private testing application (called “com.openlocate.example”) in the GooglePlay Store to allow a panel of testers to evaluate the beta-test SDK in the private, testing application

Exodus meanwhile reports a list of mobile apps that have been tied to OpenLocate at one point.

XMode SDK

The EFF reported that Apple and Google banned the X-Mode SDK from their respective app stores.

From the EFF’s article:

Last fall, reports revealed the location data broker X-Mode’s ties to several U.S. defense contractors. Shortly after, both Apple and Google banned the X-Mode SDK from their app stores, essentially shutting off X-Mode’s pipeline of location data. In February, Google kicked another location data broker, Predicio, from its stores.

We’ve written about the problems with app-store monopolies: companies shouldn’t have control over what software users can choose to run on their devices. But that doesn’t mean app stores shouldn’t moderate. On the contrary, Apple and Google have a responsibility to make sure the apps they sell, and profit from, do not put their users at risk of harms like unwarranted surveillance. Kicking out two data brokers helps to protect users, but it’s just a first step.

Data sourcing method 3: mobile apps send user data without using SDK

The third way is when a mobile application sends their users’s location data to a data broker without the use of the SDK. This third method is less scalable from the perspective of a data broker (since it’s easier to broadly distribute a SDK). But it’s also significantly more difficult to detect. Once the location data leaves the device, you can only detect its immediate destination. When the data lands on a server outside your personal device, it’s impossible for both the user and mobile phone manufacturer (i.e. Apple and Google) to track where it’s going or what it’s being used for.

There is a a lot of secrecy surrounding what mobile applications are doing this.

Life360

Life360 provides a mobile application meant to help parents keep tabs on their families.

There was a 2013 TechCrunch (puff piece) article boasting Life360’s user count:

Comparing the user counts of Life360 and Foursquare doesn’t make very much sense on face value. But the picture becomes clearer in the context of the location data industry.

In the article the Life360 CEO says the following:

“A lot of times, when people think family location, they immediately think tracking, and we’re trying very hard to shake those connotations…When users use us, it’s much more like a family network users use to coordinate their daily lives.”

That quote aged like milk. In 2021, The Markup reported that Life360 was selling families’ location data to brokers:

The Markup was able to confirm with a former Life360 employee and a former employee of X-Mode that X-Mode—in addition to Cuebiq and Allstate’s Arity, which the company discloses in its privacy policy—is among the companies that Life360 sells data to. The former Life360 employee also told us Safegraph was among the buyers, which was confirmed by an email from a Life360 executive that was viewed by The Markup. There are potentially more companies that benefit from Life360’s data based on those partners’ customers.

Life360 also sells their own location tracking devices now:

These “Tile” trackers are being called out in a class action lawsuit.

What’s this data used for?

Much of the bad press around location data involves governments buying and using the data because the Freedom of Information Act gives watchdogs and journalists a glimpse into government spending. The private sector does not receive nearly as much bad press. This lack of prominent public examples does not indicate there is no bad behavior. As the saying goes, “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

Some of the largest data brokers, like Transunion, have an enormous impact on an individual’s economic health, influencing access to competitive credit and insurance policies.

Civil rights laws protect groups from financial discrimination based on race, religion, and other variables. But studies show that location data can be used as an effective proxy to surmise someone’s identity and race. Despite this reality, financial services companies are allowed to use mobile location data in models to price insurance or calculates an individual’s interest rate.

Personalized marketing, investment research, and improving services

Most location data buyers are looking to understand their consumers’ behavior based on their movement patterns. This data informs decisions to measure and personalize marketing, inform investments, and improve products and services6.

The data sold for these use cases can be device-level data, or it be can rolled-up (i.e. 1 row of data = a group of devices, for a given hour, resolved to a specific point of interest or area of interest7).

This type of data is typically held by large technology or telecomm companies8. Commercially available location data (provided by data brokers) can help neutralize the competitive advantage of large companies holding outsized amounts of consumer data.

Surveillance

Data brokers have also found a market in surveillance-related use cases. From the early 1900’s to present day, the US has been increasingly sacrificing civil liberties (particularly privacy) in the name of safety and security9.

These use cases are controversial because many people do not agree on making this trade-off. It also begs the question security for who? And at what cost?

If law enforcement wants to get a wiretap or location records from a telecomm company, the law requires they obtain a warrant. Buying commercially available location data bypasses this requirement. Despite mobile location data and cell tower location data providing the same function, law enforcement is able to track people without needing a warrant. This is effectively a legal loophole that Congress is working to close10.

Surveillance-related use cases require data at its most granular-level (i.e. 1 row of data = an individual’s device and location at a given timestamp).

The data brokers selling device-level data for surveillance use cases are particularly secretive. This makes sense if you consider the following:

Data brokers don’t want to land in hot water since this is a controversial practice — public opinion is generally against it and it is a legal gray area.

Data suppliers (i.e. mobile apps) don’t want to land in hot water11 — if users discovered that a certain app was selling their data and it was ultimately being used for surveillance, chances are most people would delete that app.

Data buyers don’t want the people they’re surveilling to know how they’re being tracked — if you’re a law enforcement agency, you lose your advantage if people know what apps not to have on their phones.

Nonprofits, academics, and public health use cases

Data brokers also supply their data to nonprofits, academic researchers, and governmental public health organizations.

Data brokers sold their data to public health buyers for the purpose of monitoring the spread of Covid-19.

Digital privacy advocates accused data brokers of “Covid-washing” — or in other words using the pandemic for good press and to justify their actions by claiming the moral high ground.

Dewey Data is a company that connects academic researchers to third party data providers — including mobile location data brokers. Dewey Data was spun out of SafeGraph.

According to reports from the EFF, Veraset (also spun out of SafeGraph) provided the DC Government with mobile location data during the pandemic.

The director of the group doing this analysis in the DC government responded:

DC Government received an opportunity from Veraset to analyze anonymous mobility data to determine if the data could inform decisions affecting COVID-19 response, recovery, and reopening. After working with the data, we did not find suitable insights for our use cases and did not renew access to the data when our agreement expired on September 30, 2020. The dataset was acquired for no cost and is scheduled to be deleted on December 31, 2021.

Veraset’s data schema is available through Datarade’s site:

What do users get out of this?

As the saying goes, “If you're not paying for the product, you are the product.12”

The location data industry is built upon an unequal and non-transparent bargain where users give up ownership of their private data in exchange for “free” mobile apps. Data buyers (both the brokers and the end-buyers) receive outsized benefits at the expense of consumers’ privacy. The consumer also doesn’t have any way to know where or how this data is being used.

A 2021 Foursquare-GasBuddy blog post specifically calls out this concept of a value exchange where a user trades their data for a “free” app:

“At a basic level, GasBuddy’s use of location tech helps people save money and time. This clear value-exchange, paired with their thoughtful approach to privacy and uncompromising focus on driving innovation in travel and mobility attracted Foursquare to GasBuddy as a strategic partner – we look forward to collaborating for years to come.”

I am saying this is an unequal bargain because I do not believe the potential safety benefits from public health monitoring or law enforcement warrantless surveillance outweighs the degradation of privacy, but that is my personal opinion.

Can mobile location data be tracked back to individuals?

Location data brokers market themselves as pro-privacy:

Studies show that device-level data is inherently personal — even if data vendors try to remove information like name, phone number, and email. It can only take a few data points to figure out what anonymous ID belongs to a specific person by deriving where they live and work.

From the widely cited 2013 article Unique in the Crowd: The privacy bounds of human mobility:

[I]n a dataset where the location of an individual is specified hourly and with a spatial resolution equal to that given by the carrier's antennas, four spatio-temporal points are enough to uniquely identify 95% of the individuals.

Companies can also pay for identify graph services. Identify graph providers, like Neustar, Amperity, or LiveRamp, provide a service to match identifiers like mobile advertising ID’s and IP addresses to personal information like full name, email, phone number, home address, etc. These services can sell to companies trying to prevent fraud, and they can also be used by scammers trying to commit identity theft. In both scenarios, the broker profits.

Cracked Labs provides an in-depth explanation of identity graphs — highlighting LiveRamp. They reference the below diagram — the dark blue represents personal identifiers and the grayish-blue represents the identifiers they can use to map back to someone’s personal identity:

LiveRamp’s documentation spells out how the mobile device ID can be used as a link to the personal/known information about a person:

An archived Datarade13 page on SafeGraph calls out specifically how location data can be integrated with LiveRamp:

What about rolled-up foot traffic statistics

In the case of rolled-up or summary location data, it is generally not possible to link back to an individual. However if a data provider does not employ differential privacy properly and reports visitor counts that are really small, there is a real risk of de-anonymizing the individuals.

Can’t Apple and Google be doing more?

Apple and Google have been criticized for not curtailing this kind of action on their app stores, so they’ve implemented additional privacy controls for users.

In a 2019 Time Magazine article, Tim Cook positions Apple as the good guys in the fight for privacy:

We all deserve control over our digital lives. That’s why we must rein in the data brokers

While on the surface, Apple and Google’s privacy features seem pro-consumer, they have been criticized as a means to hoard data in order to stifle competitors and increase the value of their advertising businesses.

They have also been criticized as half measures because if Apple and Google allow you to change your device ID or prevent it from being shared, app developers and data providers can bypass this by creating a composite ID that “fingerprints” your device (e.g. by combining IP address, default browser, dimensions of screen size, they can confidently pinpoint a unique device).

Additionally, even if Google and Apple thoroughly inspected an app’s source code and didn’t allow it to directly transmit user locations to a known data broker, nothing is stopping the app from collecting the data on their own servers then transmitting it to the data provider after the fact (outside the app itself - therefore bypassing detection).

Apple and Google seems less interested in solving the privacy and safety problem for users and more interested in shifting liability away from them.

There are different types of data brokers — but are there really?

Let’s take a closer look at the 2 main types of location data brokers. There are companies that sell device-level data and ones that sell rolled-up or summary data.

The granular data is much more sensitive than the rolled-up, however it’s important to note you cannot create the rolled-up data without initial access to the granular data.

There are also different customer markets for device-level data vs summary-level data.

In many occasions, a single company will offer rolled-up or summarized location data, but will act as the holding company or parent company of a device-level data broker. Mergers, spin-offs, and rebrands are common practice in this industry14.

The "rolled-up" data broker is the public-facing brand and the granular data broker is more likely the esoteric, shadowy brand with minimal online presence (for the reasons stated in the previous section).

So why hide the ball and split up operations into a public-facing brand and a secretive one:

create a front door, public-facing brand to attract customers, then refer them to the under-the-radar device-level company for use cases requiring more granular data

avoid or rebut bad press related to device-level data that will hurt sales and reputation

recruit employees who might have qualms with the shadowy-side of the industry

shield and contain liability

the public company can deny any wrongdoing or allegations because it is a “different” company than its device-level sister company (which is legally accurate, but functionally not really…)

the public brand can claim they “partner” with the device-level company — this creates perceived distance, even though the companies may be owned and operated by the same people

if the device-level data company goes under or is sued, it doesn’t take down the public brand

having 2 corporate entities can help skirt existing (often toothless) privacy regulations

Possible solutions

There are multiple angles to consider when address the location data privacy problem.

Sell-side: restrict how device-level user location data is sold

Buy-side: restrict how device-level user location data is bought and used

Collection-side: restrict how device-level user location data is collected

Attempts at regulatory solutions

Members of Congress have attempted to address this issue, dating back to 2011.

From Wikipedia:

The Geolocation Privacy and Surveillance Act (GPS Act) was a bill introduced in the U.S. Congress in 2011 that attempted to limit government surveillance using geolocation information such as signals from GPS systems in mobile devices. The bill was sponsored by Sen. Ron Wyden and Rep. Jason Chaffetz.[1] Since its initial proposal in June 2011, the GPS Act awaits consideration by the Senate Judiciary Committee as well as the House.

The only current proposal in 2024 for action is The Fourth Amendment is Not For Sale Act.

This act primarily addresses the buy-side. It seeks to restrict law enforcement from purchasing device-level location data without a warrant.

I think that’s hard to argue against. There is a reason warrants exist — they empower law enforcement to gain information relevant to criminal activity, and they require approval from a judge. Bypassing this process goes against the fundamentals of the US criminal justice system.

Banning law enforcement from purchasing commercially available location data is a good step, but it’s an incomplete solution.

Law enforcement bypassing warrants isn’t the only risk to peoples’ privacy and safety.

Criminal organizations and adversarial foreign governments are smart. There are many examples of bad actors using shell or front companies to get access to technology and data they are “not supposed to”:

According to the US Treasury:

OFAC sanctioned Mabrooka Trading Co LLC (Mabrooka Trading) – based in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – and its China- and UAE-based network that have been involved in procuring goods for Iran’s ballistic missile program. This network obfuscated the end user of sensitive goods for missile proliferation by using front companies in third countries to deceive foreign suppliers.

The Treasury’s press release mentions these front companies are trying to “deceive” foreign suppliers. But when a supplier is incentivized to sell their product, are they not incentivized to look the other way and close the sale?

Allowing the uncontrolled sale of large amounts of peoples’ private location data is a safety issue.

The location data problem has been tightly coupled with the overreach of law enforcement problem — and while that is a valid concern, this approach hasn’t resulted in any passed legislation.

The location data problem needs to be reframed as a consumer safety issue:

Safety from criminals, like scammers and stalkers

Safety from state actors, both foreign and domestic

Safety from corporate greed and discriminatory practices, like redlining

I want to expand on the Fourth Amendment is Not for Sale Act by proposing that location data be treated like healthcare data, and addressing both the collection- and sell-side of the problem.

Treat location data like it’s health data

Like health records, where someone spends their time is deeply personal and needs to be treated with respect. Location data contains so much latent information — a person’s religion, ethnicity, closest friends and family, income, and more can be accurately predicted if you have access to their phone’s location pings.

Location data is, in a way, also health data. It can reveal where someone receives healthcare, whether or not they go the gym, and where they shop or go out to eat.

Additionally, according to A Systematic Review of Location Data for Depression Prediction:

Location data explain the movement patterns and activity of participants and can predict the severity of depression with high accuracy

Device-level data in not anonymous and it’s very personal, and I believe this data should be treated like it’s health data.

Collection-side: deterring companies from storing peoples’ location

Do mobile applications need to save peoples’ sensitive location data in the first place?

For example, a navigation app could take the user’s current location and tell them what restaurants are nearby — at no point does the app need to keep a running log of this user’s locations.

If we treated location data with the same regulatory protection as health data, very few mobile application would go through the trouble of saving (let along selling) peoples’ location data.

For mobile applications that do persist records of user locations, I think they should follow similar procedures as what HIPAA requires of health data.

The federal law, HIPAA, mandates handlers of patient data to have strict access controls and an audit log of anyone who has accessed the data15. Even if device-level location data has a person’s identity obfuscated, it does not take much effort to reverse engineer who the person is. For example, if you take the two most common locations a person visits, you now likely know their home address and place of work — which you can combine with public records or online information to identify them.

Having a location data-specific regulation, similar to how HIPAA treats health data, would disincentivize companies from needlessly storing peoples’ location data, and when it is stored, it would help safeguard the data and promote responsible use.

Sell-side: ban device-level location data reselling if the user is not directly aware and compensated (similar to a Nielsen Family)

If a company has your device-level data, it should only be because they are offering a location-based service, where you are fully aware they are using and storing your location data. If you give your data to a ride sharing app because it’s a useful service, and the app stores and uses your location data to improve their service, I think that is totally reasonable as long as they protect that data (subject to a HIPAA-like law) and do not resell it.

The only scenario where I think it would be appropriate for device-level data to be resold is if someone explicitly allows a company to sell their data and receives direct compensation. A model for this is the “Nielsen family.” The Nielsen family agrees to have all their TV-viewing monitored so that Nielsen can report statistics on viewerships to help advertisers reach their target audiences. In exchange, Nielsen families get compensated. If an adult wants to explicitly let a location provider track their location to then sell to other companies, I think that is fine, as long as the following criteria are met:

The person gets directly compensated

They are educated of the risks of selling their data — including any potential risk posed to those around them (i.e. if they are often with another person who doesn’t want their data shared, that indirectly could violate the other persons’ right to privacy)

They are notified of what company buys their data and the intended use

It is illegal for the company buying the location data to then resell it — because then the original person loses the audit trail of where the data is going and how it is used

What about aggregated (i.e. non-device-level) location data?

This data is inherently less sensitive because it can’t be tracked back to an individual person (unless the data provider does not take sufficient anonymization methods). However these foot traffic statistics are generated based on device-level data, which was collected without meaningful consent or compensation. For that reason, I believe this type of data should also be treated like the Nielsen family model I described above.

Closing thoughts

As I am wrapping up, I wonder if location data privacy should be regulated separately or if it should be addressed under a comprehensive AI safety, fair use, and data privacy law.

On one hand, I think passing current proposals, like The Fourth Amendment Is Not for Sale Act is a necessary step. However it is only a downstream solution addressing one type of data (i.e. location data) for one type of buyer (law enforcement). There is a much larger dynamic at play here. It involves the fairness and transparency of data supply chains and the safe application of data and AI.

It might be more fun and profitable to move fast and break things. But I believe deliberate and thoughtful development is key to building a future where technology improves, rather than degrades, the human condition.

Partially due to succesfully manipulating Congress through lobbying and fooling the public through vague click-though terms of service.

I’m going to use the term data broker and data provider interchangeably. Broker implies the company has no direct relationship with the people whose data is being collected. Broker generally has a more negative connotation and is typically used by the media or consumer protection groups. Provider sounds friendlier and is how the companies brand themselves. The distinction is nuanced because a company can both collect information directly from people (i.e. through their own mobile app) while also buying compiling location data from multiple mobile apps that they don’t control.

While a large app, like Facebook, isn’t likely to sell all their location data to a data provider, a small/medium app that requests your location and is likely free to download (e.g. an app that helps you find cheap gas or a weather app) is happy to sell your data.

When most users select to share their data, they are not reading the vague terms and conditions of the app. Even if they did take the time to read the T&C’s, it is not clear where their data is being sent and how it is ultimately being used. Although a user technically consents to their data being shared, the consent isn’t meaningful if they have no way of knowing where their data is going or how it’s being used.

California runs a data broker registry. This isn’t specific to location data brokers. The largest location data brokers include Foursquare (+ acquired company Placed), SafeGraph (+ sister company Veraset), Gravy Analytics (+ acquired company Unacast), Near (which actually went public before delisting - this means they filed a public S-1 and other SEC reports).

By contracting with tens, hundreds, or thousands of small/medium app developers, data providers are able to create a mosaic of user locations (called a panel) that rivals the user counts of large apps.

The panel is measured by daily active users (DAU) or monthly active users (MAU), depending on how often they deliver the data to their customers. The panel size will fluctuate over time as users stop sharing their location with a given app, or new users begin sharing their location. The data provider will offer statistics on their panel size and composition, which allows buyers to extrapolate the panel’s behavior to the whole population. For example, if the panel represents 10% of the US population, and the data reports 25 people were in a specific grocery store at 2:07 pm, you can infer that around 250 people were actually in the store at 2:07 pm.

You can learn more specifics about these use cases by going to location data brokers websites and reading their customer stories/testimonials — most of the use cases are ad measurement, site selection, investment research, enriching web-based mapping applications, etc.

User locations are usually overlaid with point-of-interest (POI) data, so that buyers can see, for example, how many devices visited a particular store.

A handful of companies have direct access to vast amounts of peoples’ mobile phone location (i.e. precise latitude and longitude) at any given time. These companies include phone and operating system providers (e.g. Apple and Google), popular mobile app developers (e.g. Meta, Amazon, ByteDance, Accuweather), and ISP’s and telecomms (e.g. AT&T, Comcast, Verizon).

The bill, H.R.4639 - Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which has passed the House, begins to address some of these concerns (such as closing the loophole which allows law enforcement to access commercially available location data without a warrant).

There isn’t anything stopping a paid app from also selling location data to bolster its revenue, but this practice is more common with free apps.

Datarade is a listing site for data providers — they claim it’s “The easy way to find, compare, and access data products from 500+ premium data providers across the globe.

Company websites often get taken down or changed after mergers, spin-offs, and rebrands, but you can use the Wayback Machine or Internet Archive to see old marketing material, customer stories, and product specifications listed on websites.

Technology solutions like data clean rooms and differential privacy are helpful but they need to be paired with regulation and enforcement to ensure privacy measures are more than just lip-service.